“Power” – it is a seductive, addictive, and a dangerous thing. And it is for this reason that the framers of the American Constitution divided it, balanced it, and checked it in the different branches of the American government. They well knew that men were not angels and that a lust for power unchecked would convulse the entire nation. Perhaps we have learned after all that it is true – that power is safest with those who most understand it and least want it.

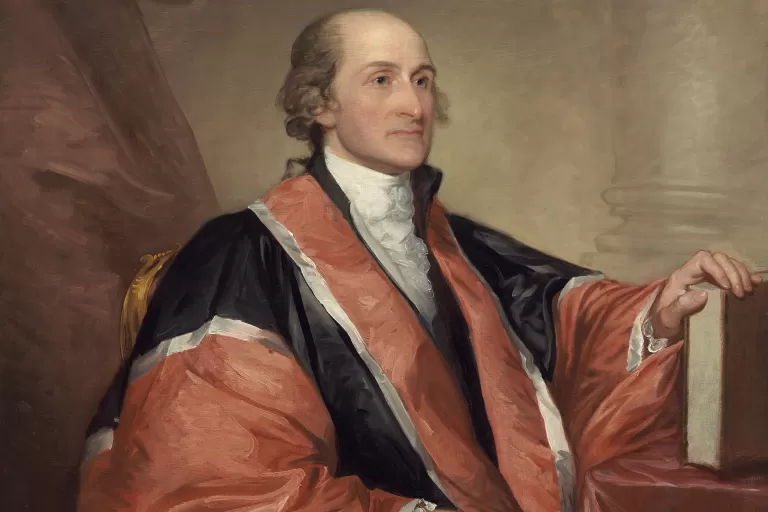

In 1792 the race for the governorship of New York “was the most violent and bitter the state had ever witnessed.” (Monaghan, Frank, John Jay Defender of Liberty, AMS Press: New York, 1935, p. 325) Henry Clinton had been governor of New York as long as there had even been a governorship. As the election approached, it was considered that only one man could defeat Clinton. That man was John Jay, one of the co-authors of the Federalist Papers. It was he who had been President George Washington’s choice for the first Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Jay was a popular man, but he was a reluctant candidate. He was not a politician, and it was not his habit of seeking public office. It was, rather, his governing philosophy that “the office should seek the man, not the man the office.” (Monaghan, p. 326.) Nevertheless, Jay was persuaded, and [he] agreed to be put forth as a candidate, but he maintained that he would do nothing to further his own election.

Well, the campaign waged by the supporters on both sides was vicious and slanderous to say the least. Only once during the campaign did John Jay speak, and then only to “curb the vehemence of his own supporters.” Monaghan, p. 331.) He remained silent and dignified throughout the campaign, not rising to his own defense, and not wishing to discuss it, even with his wife.

Well, the election was held on April 24th, 1792. The results were slow to trickle in. By May 2nd, Jay’s supporters who were watching had “little or no doubt that the election [was theirs]” (Monaghan, p. 333.) But the Clinton supporters were not to be defeated so easily. They found a legal loophole, a technicality. In Otsego County, New York, Jay held a comfortable majority. Now, according to the law, the county’s ballots were to be transmitted to the Secretary of State by the county sheriff. However, the term of the old sheriff had expired and a new sheriff had not yet qualified for the office. The ballots were therefore given to a special deputy to be delivered. The ballots were sealed, they were legal, and they were legitimate; and if they were accepted, the incumbent governor, Henry Clinton, would be ousted, and John Jay would be the next governor of New York. Clinton and his supporters pounced on that technicality, and argued that the Otsego ballots and those of other counties that Jay had won could not be accepted because they were not properly delivered. Clinton’s supporters rousted an army of lawyers seeking every justification and argument that could be contrived to support the action.

The election officials charged with ruling on the matter were partial to Governor Clinton. On the basis of that contrived technicality, they ruled the ballots void and unacceptable, and then burned them. Governor Clinton won the election by a margin of 108 votes. The supporters of John Jay were incensed by the injustice and vowed to fight. The disenfranchised citizens of the wronged counties were especially angry at what they considered enslaving tyranny, and they vowed to seek every legal redress at their means. The talk even turned to threats of serious violence. In short, all of New York was in a state of angry commotion.

And through it all, what of the patriot, John Jay, who had so nobly lauded the principles of the Constitution, and helped bring about its ratification in New York? When John Jay came to New York City, he was met by an “immense concourse of citizens . . . who escorted him into town. Cheering groups lined the road[s] . . . A federal salute was fired” (Monaghan, p. 338-39.) on his behalf. Jay stood to speak amidst the cheers of his supporters, but their prolonged and thunderous applause drowned out his voice.

Now, consider that moment! If Jay had given the word, his supporters would likely have fought to the courts and perhaps even to the death in his defense. So determined were they that he be their governor, and all of it sits in his hands. So what did he say? With all that power at stake, what did Jay do?

He turned to that crowd and he told them “no political differences should suspend or interrupt that mutual good-humor and benevolence that harmonizes society.” (Monaghan, p. 339.) In short, he urged all who would listen not to act illegally, and not to sacrifice the good of all for the gain of power. Because of John Jay “the enthusiasm to remove Governor Clinton was never translated into action.” (Monaghan, p. 340.) And Clinton served his term as governor.

It is particularly inspiring what John Jay said when the controversy erupted. To his wife he wrote these immortal words that I hope we in this republic would always remember - and this is my point. He said, “A few more years will put us all in the dust; and it will then be of more importance to me to have governed myself than to have governed the state [of New York.]” (Monaghan, p. 337.)

My friends, I conclude with this: It is better to be right with God than in power with man. As God lives, may it be so with us, and with those who lead us, I humbly pray.

Story Credits

Glenn Rawson – November 2000

Music: The Great Deep (edited) - Jay Richards

Song: America the Beautiful - The Mormon Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra